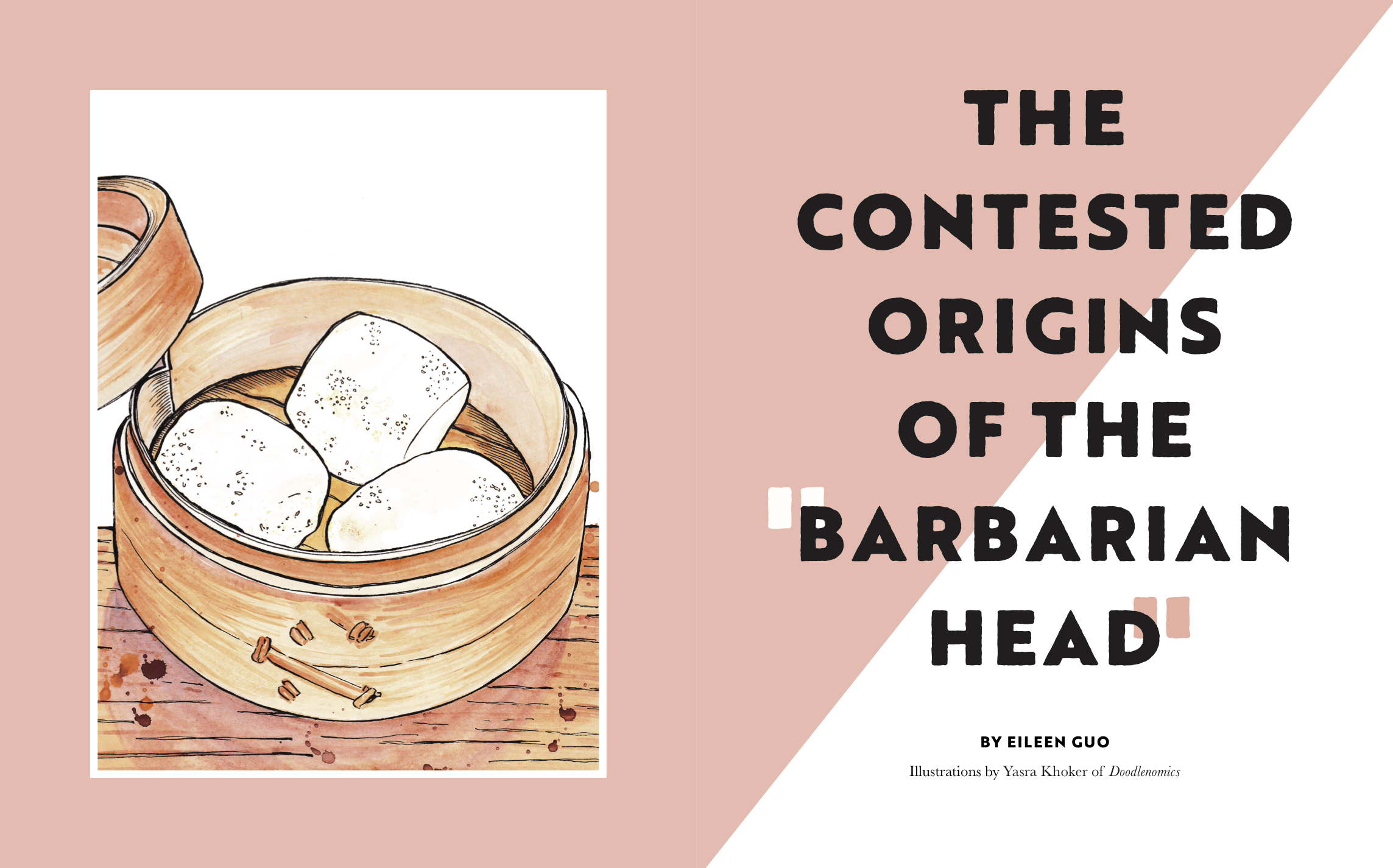

Chinese mantou (馒头) is unassuming. In its most basic form, the fist-sized steamed bun contains four ingredients: yeast, flour, salt, and water. Its taste is light and unobtrusive, its texture smooth on the outside and fluffy on the inside: just right for its role as a foundation for the richer flavors of a Chinese meal.

Most commonly prepared steamed and plain, mantou can also be deep fried, dunked in condensed milk, and filled, though today, Chinese mantou are typically unfilled. Bao, with either savory or sweet fillings, are the stuffed versions.

In The Origin of Things, written during the Northern Song Dynasty (AD1127-1279), Gao Cong describes how the earliest documented appearance of mantou dates back to China’s Warring States Period (AD 220-280), during which three kingdoms vied for control of ancient China.

As Gao described, Chancellor Zhuge Liang, a brilliant political strategist of the Shu Kingdom, was returning from a campaign against a group of Southern ‘barbarians’ when faced with a particularly turbulent river crossing. According to local tradition, the only way to safely complete the crossing was to appease the river gods with tributes of decapitated heads. Unwilling to resort to human sacrifice, Zhuge instead ordered his crew to fashion animal heads out of wheat dough and meat fillings. The River Gods were fooled, the ships crossed safely, and his doughy creations became known, thereafter, as ‘barbarian heads’.

But even with this origin story, the characters assigned to mantou – “Barbarian Head” – is unusual in Chinese food nomenclature. Historically, Chinese foods were named for their major ingredients or poetically to stimulate the appetite. “Barbarian Head” certainly does not fit within this convention. According to some scholars, this suggests that Chinese characters were lent for a food name lent from another language.

And, with this interpretation in mind, a better source for the origins of mantou may be “Soup for the Qan”, a medicinal cookbook written by Uighur imperial doctor Hu Sihui for the Yuan Dynasty (AD 1279-1368) Mongol emperor that he served (direct descendants of Genghis Khan), which mention a dumpling-like dish similar to mantou. The early mantou had stuffing – more like modern-day bao (包), a name that came into use later on,.

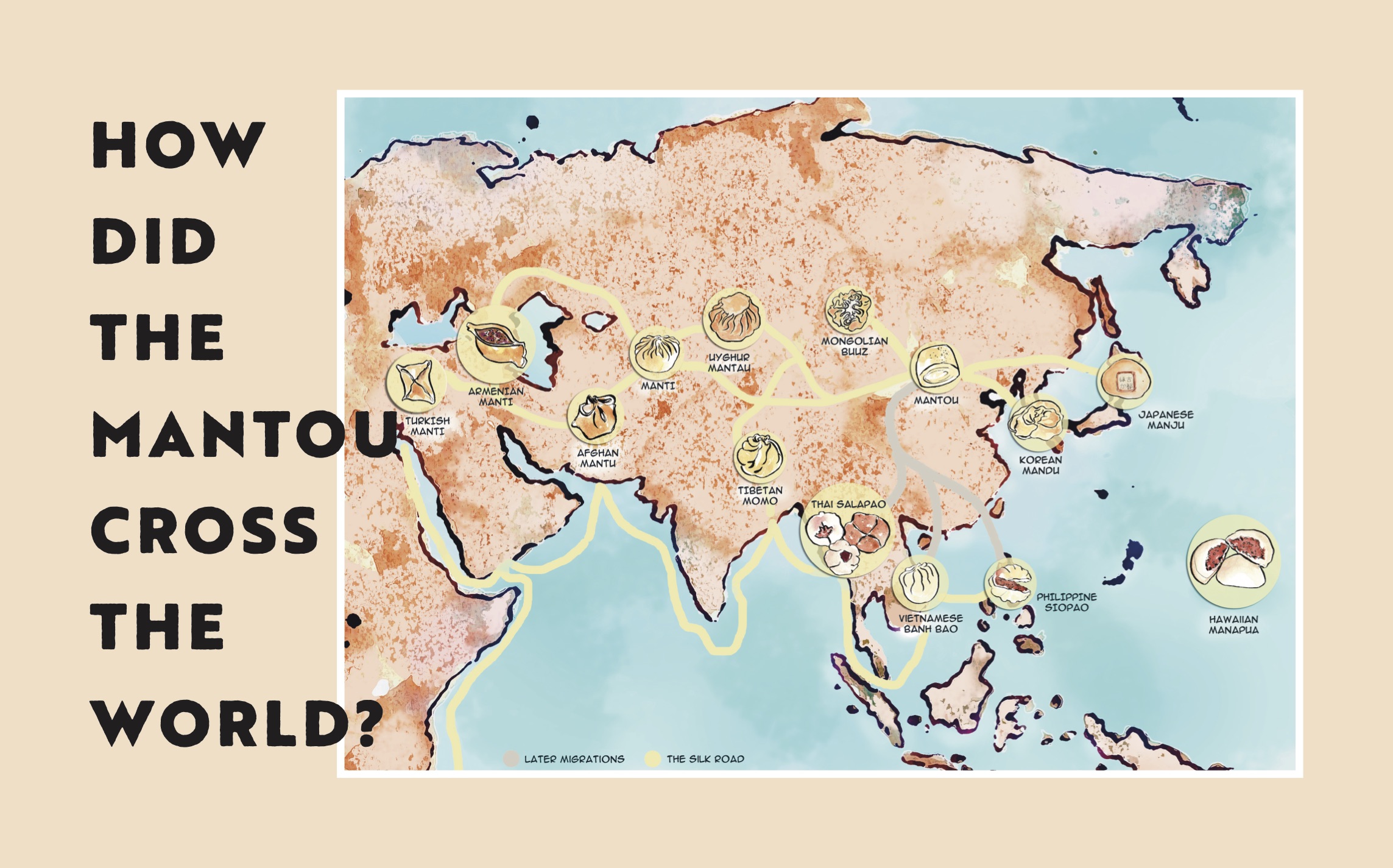

It was during the thirteenth century that the conquering Khans of the Yuan Dynasty spread the stuffed buns – prepared beforehand and carried on horseback as an easy-to-cook meal – around their empire.

Today, Korea has mandu (which refers to both stuffed and unstuffed buns) and Japan the manju. Turkey claims manti as a native food, while Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan all prepare stuffed mantu. Mongolia has both filled buuz and unfilled mantuun buuz, which it considers a national cuisine, but which likely descended from the Chinese stuffed bao and mantou, respectively. Meanwhile, Tibet and Nepal consume stuffed momo, a word that also originated in China’s Jiangnan region, where momo (饃饃) simply means unstuffed bun. Even further afield, Vietnam, prepares the banh bao, the Phillipines the siyopaw, Thailand the salopao, and, centuries later, variations have even reached Hawaii as the manapua.

But in these languages, the mantou cognates have no native meanings, suggesting that despite their enthusiastic adoption – and claiming – of mantou as their own, its origins lie elsewhere, likely to the Uighurs in China, who have a traditional dish called mantau, which means ‘bread prepared in steam’ in their native tongue.

But even here, scholars have noted the lack of clarity around their origins; Josh Wilson and Andrei Nesterov wrote for the School of Russian and Asian Studies: “They are considered native to Central Asia, but are also thought to have descended from a still-older Chinese dish.”

But Wilson and Nesterov may not have been referring to mantou; the Chinese first began eating a steamed fermented dough during the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) and the bing, a flat, unleavened bread that has been prepared since the time of the Song dynasty.

Ultimately, the question of mantou’s origins might be a chicken-or-the-egg-like mystery. Certainly, mantou’s contested historical roots had no bearing on my own experiences of them growing up – nor, I suspect, that of other ‘native eaters’. In my Chinese-American household, from of Sichuan Province, the modern-day location of Zhuge Liang’s ancient Kingdom of Shu, mantou was a staple at our breakfast table.

My parents tore PacMan-like seams into their buns, fashioning mini-sandwiches around pickled vegetables, or dipping them whole into their congee. I preferred bao but ate mantou plain, pulling apart the fluffy innards with a child’s delight at the sanctioned destruction of food before eating it. In the winters, I jostled for comfort on our couch with containers of rising mantou dough, buried behind the pillows to help it rise more quickly, as our living room filled with a subtle sweetness.

I didn’t give mantou much thought until my mid-twenties, when I spent two and a half years in Kabul, Afghanistan working in international development. During many meals with Afghan friends, they proudly presented a local delicacy called mantu, a steamed dumpling with a thin dough shell around a ground beef or lamb filling mixed with minced onions and spices, and served with a garlic yoghurt and tomato sauce.

I was immediately drawn to Afghan mantu, not for its taste – the yoghurt and tomato combination was slightly sour – but because its name reminded me of home, of childhood, and even of the rise and fall of empire. This region of the world was once great, as the spread and evolution of mantu from mantou on the old silk road demonstrated, and it could be again. As an aidworker in Kabul, this was something I needed to believe.

But this, I suppose, is the power of food: it serves as a connecting thread through cultures, history, and – sometimes – our own lives.